Between 1843 and 1853, the British colony of New Zealand sent an estimated 110 convicts to the colony of Van Diemen’s Land, present day lutruwita Tasmania.

These convicts came from a range of backgrounds: British soldiers, sailors, criminals, Māori political prisoners and prisoners of war.

One of the best recorded stories of convict transportation is that of Hōhepa Te Umuroa and the four Māori prisoners of war, exiled to the penal colony of Maria Island off the coast of Tasmania.

Sentenced to life in prison, they were transported to Van Diemen’s Land for their involvement in ‘Te Rangihaeata Resistance’ on the British colonial outpost of Hutt Valley in the Wellington region of New Zealand in 1846.

On an early morning on 16 May 1846, a group of Māori men led by Te Rangihaeata of the Ngati Toa iwi walked towards the British colonial outpost of Hutt Valley. Their objective was to attack Boulcott’s farm, where two regiments of British soldiers were stationed.

Using the element of surprise, the Māori resistance fighters charged down the valley toward the farm. The battle was short lived, leaving six British soldiers dead.

From a distance, but in clear view of the farm, the Māori resistance fighters performed a war haka celebrating their victory before leaving into the hills.

On 14 August, several months after Te Rangihaeata Resistance, Te Umuroa was captured along with six other Wanganui men. The men were sentenced on 12 October, charged for ‘rebellion against the Queen of England’.

Te Umuroa and four others were exiled as prisoners of war to Maria Island off the coast of Tasmania.

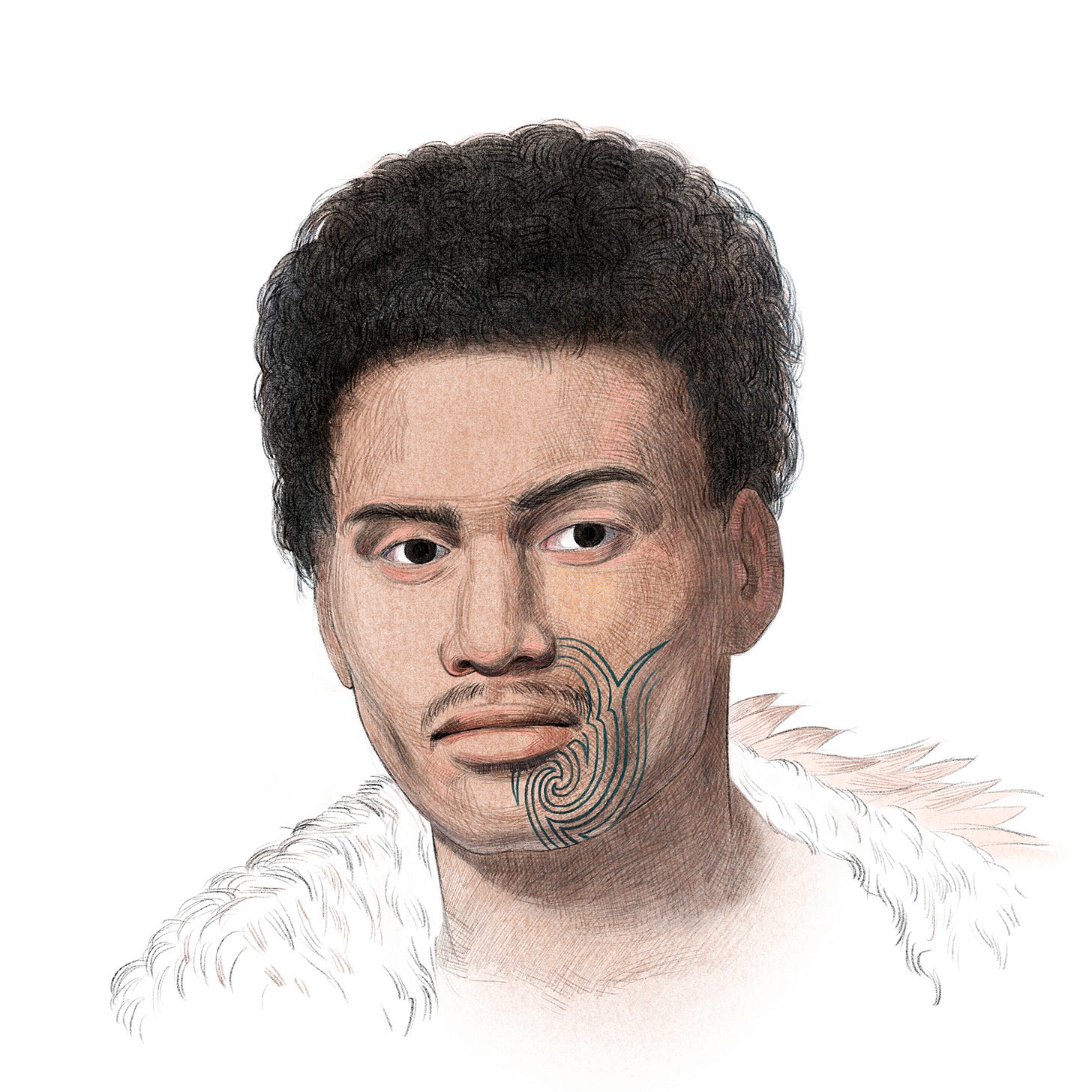

When they arrived in Hobart on 16 November the men were met by a large crowd because they were dressed in traditional Māori clothing which most Tasmanians had never seen. They stayed in the Hobart prison while in transit, where the artist John Skinner Prout drew all five men in their traditional Kākahu cloaks. Young Hōhepa Te Umuroa was distinct from the other Māori men as he was captured before his tā moko facial tattoo was completed.

After Hobart, the men were sent for hard labour in Darlington on Maria Island. In mid April of 1847, while working on the construction of a building, Te Umuroa became sick with tuberculosis.

On the 19th of July, 1847 the prison foreman, J. J. Imrie, wrote in his diary:

At 4 am visited the Maoris. Found Hōhepa very nearly gone. At 5 am he breathed his last breath without a struggle.

Shortly after Te Umuroa’s death, the men were pardoned for their crimes and returned to Aotearoa New Zealand.

Te Umuroa was buried in the public cemetery in Darlington on Maria Island, facing across the ocean towards Aotearoa. His gravestone was inscribed in Te reo Māori language.

In 1988, Te Umuroa’s body was repatriated by the New Zealand Government to Whanganui in Aotearoa after three years of negotiations with the Australian government.

Hōhepa Te Umuroa’s grave still remains on Maria Island. The story of Hōhepa Te Umuroa remains important to Māori people today.

REFERENCES

https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/warriors-legend-shapes-operatic-journey-20120219-1th7a.html

https://convictrecords.com.au/convicts/te-umuroa/hohepa/130572

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/TAH196009.2.13

https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1t80/te-umuroa-hohepa

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG171323

Aboriginal convicts: Australian, Khoisan and Maori exiles, 2013 Kristyn Harman